Tag Archives: Women Photograph Men

30 For 30: A Lady, a Truck, a Singing Dog

To celebrate Women’s History Month, we’re featuring items from the PWP Archives* each day on this blog. In looking back, we see not only where we started, but how far photography, women, and the world have come since 1975.

Photography books weren’t common in the 1970s, and getting one published was hard, especially if you were a woman. So PWP’s founder, Dannielle Hayes, had to get creative. In 1976, she put out a call on the theme of “woman photographs man” and received hundreds of photos. Then she wrangled a truck, drove it into Rockefeller Center between 49th and 50th streets, and with the help of volunteers, set up two projectors (courtesy of Kodak) and a rear projection screen. She ran the images throughout the day, along with a tape of herself talking, musical interludes, and a “singing” (actually barking) dog.

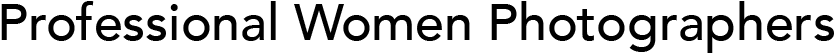

People took notice, including an editor at William Morrow Fairchild, and Hayes was offered a contract. Women Photograph Men was published in 1977 to great reviews.

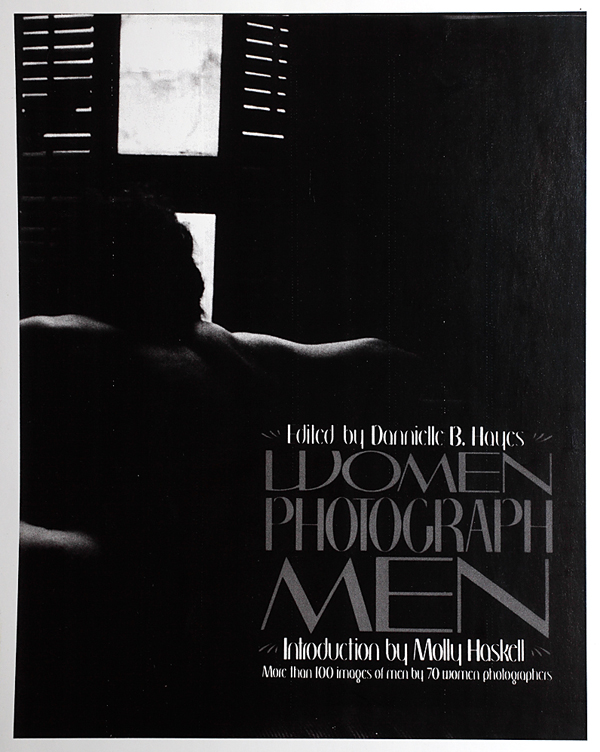

But not without drama. Lawyers for the publisher warned Hayes that she would be responsible for any lawsuits arising from the male nudes. Her response: “the little blue-haired lady from the Midwest will love these.” There were no lawsuits, and a similar book, Women See Men was published a few months later. These were the first or some of the earliest anthologies to feature the work of women photographers. Change was in the air; the sisters were stepping up and doing it for themselves.

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

*The PWP Archives were acquired by the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library of Emory University

Links to all the 30 For 30 Women’s History Month blogs:

Help Me Please! Hopelessly Waiting…

Exhibition and Anger

Spreading the Word

Early Ads On Paper

Cards and Letters

A Lady, a Truck, a Singing Dog

Women of Vision

A Show of Their Own

Taking It To the Street

Sisters of Sister Cities

Sold!

Education and More

Face of a Changing City

Digital Enabling

Expanding Walls and Other Possibilities

A Wonderful Life–Lady Style

Branding–the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Great Change Sweeps In

PWP Goes Live!

Honoring the Upcoming

Continuity Through Change

Reaching Out

Eye a Woman Naked

Rapidly Multiplying Alternative Options

Women In the World, As Themselves

Kudos!

Friends Who Overcame and Inspired

Reversing the Gaze

Photography and More

Chicks Telling It Like It Is

Looking Back With Thanks

Midcentury Majesty: Frances McLaughlin-Gill & Friends

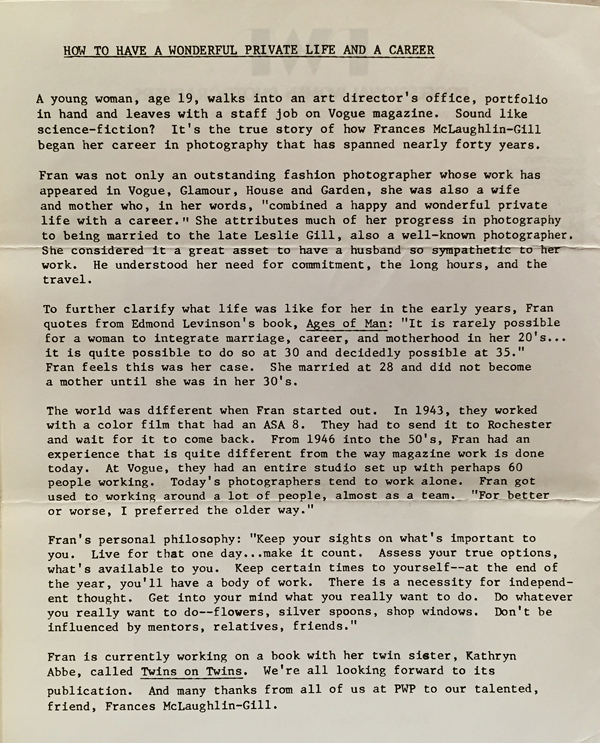

Working on the PWP Archives, one name kept cropping up in the early documents: Frances McLaughlin-Gill. From brief mentions, I gathered that she was one of the first members, had a successful career photographing for magazines, and was involved in a project about twins. Other than that, she remained a mystery, someone I hoped to learn more about, but never did.

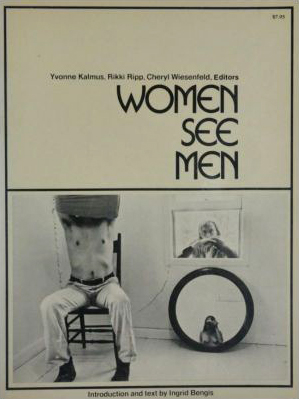

So when PWP’s founder, Dannielle Hayes, sent an invitation for a show featuring her work, I was thrilled. Midcentury photographers are having a moment. There is the great Irving Penn show at the Met, and now Lives & Still Lives: Leslie Gill, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, and Their Circle at the Howard Greenberg Gallery. Much will be written by far smarter people, but I can share a few items from the PWP Archives that shed light on the spirit of the time and on the spirited life of Frances McLaughlin-Gill.

Frances McLaughlin-Gill and her twin sister, Kathryn, were born on September 22, 1919 in Brooklyn, and were only three months old when their father died. The family moved to Wallingford, Connecticut, where in 1937 Frances was valedictorian of her high school class, with Kathryn the salutatorian. Both twins enrolled at Pratt Institute where they studied photography, and in 1941, found themselves among the five finalists in the Vogue-sponsored Prix de Paris contest.

After working briefly as a stylist, Frances McLaughlin was signed by Alexander Lieberman in 1943, making her the first female fashion photographer under contract at Vogue. She flourished, bringing to her work a sense of movement and spontaneity that was in sync with the fast-paced time and the changing role of women in it. According to her daughter, Leslie: “Frances’s photos were based on improvisation. By placing her models in impromptu settings, she fostered a dynamic atmosphere of interaction between her subjects, the city and the viewer. At Vogue she was able to use this technic to realize her livelong interest: revealing modern woman’s complex role in society.”

In 1948, Frances McLaughlin married Leslie Gill, a photographer who worked closely with Alexey Brodovitch of Harper’s Bazaar, and was among the first to experiment with color film and the use of strobe. “Each flourished, though in different ways,” said their daughter, which made for a beautiful partnership that was far ahead of its time. There was a meeting of minds, as well as the synergy of their careers, each partner supporting and inspiring the other. It was very modern and progressive, and very much in keeping with the spirit of Frances McLaughlin-Gill.

Entering the Greenberg Gallery, you feel as if you’ve have been swept back to a vibrant Midcentury scene, where modern women, clothed like goddesses, float in a realm of sculptured light and regal silence. They are of the real and the imagined, conjured by photographers in whom a sense of elegance seems to have been innate.

Like the others in this group which includes Irving Penn, McLaughlin-Gill made images that resonate beyond fashion. Several were shot in a makeshift outdoor studio, and in the dappled sun and classic clothes, is the sense of a Cheever yard, the casual moment bearing a refinement seldom seen in print today. You imagine the models returning to the Barbizon after the shoot, or heading off for an evening at El Morocco. The couture gowns, the post-War energy and elegant people, the brash city stepping into its role as capitol of the world, these visions refresh yet make you long for a vanished time. It had magic, as did the photographers who captured it.

Some images are black and white, others in color; running through all is a sense of balance and portion that echoes the abstract paintings of the day. You feel their shared concerns: the need to energize the still life genre, to capture group dynamics without losing the air of regal calm, to integrate color without compromising form. They very much succeeded, and in their work is the sweep and majesty of lost and grander time. We appreciate, but also look back and mourn.

In 1958, McLaughlin-Gill’s husband died when their daughter was just three months old, repeating her father’s terrible fate. But with strength and art, she went on. She worked for Glamour, House & Garden, and British Vogue. She produced and directed independent films, and taught at New York’s School of Visual Arts where, according to master printer Sid Kaplan, “she was not liked, she was loved.” She also exhibited her images, participating in the 1975 landmark exhibition Breadth of Vision: Portfolios of Women Photographers at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. It was the largest show of its kind, featuring over a hundred female photographers, including Mary Ellen Mark, Susan Meiselas, Barbara Morgan, Eva Rubinstein, Suzanne Opton, PWP’s founder Dannielle Hayes, and Dianora Niccolini, PWP’s first president.

After the show some of the participants kept meeting, a group that eventually became Professional Women Photographers. According to Dannielle Hayes:

“Franny was an early PWP member in 1975 when we were still meeting in my living room. For the International Women’s Arts Festival, she helped organize our one day exhibit called WOMAN PHOTOGRAPHS MAN by arranging for a truck to pull into Rockefeller Center. We ran an electrical line from the AP office to the truck which powered two donated Kodak carousels and a dissolve unit, plus a funny tape that combined an interview with me, some music, and a singing dog. Rear screen projection showed five images by each of the women photographers. While none of the invited publishers stopped by, I was put in touch with an editor at William Morrow & Company, so packed up the photos, tape with singing dog, and marched off to meet her. Franny went with me. Within 20 minutes, we were talking about a contract. Franny said she’d never seen anything happen so fast.”

“The resulting book, WOMEN PHOTOGRAPH MEN, was published in 1977 and received much acclaim in the US and abroad. Each of the women photographers received $25.00 paid from the advance, plus a hard cover copy of the book. We had an exhibit at ICP (then uptown on 5th Avenue), and the photos are in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as ICP.”

A few years later Hayes helped McLaughlin-Gill and her sister, Kathryn Abbe, put together their book Twins on Twins. All were included in Women of Vision, a book produced by PWP’s first president, Dianora Niccolini. Women helping women, making opportunities, moving ahead in large steps and small in a field where they were not always common or welcome.

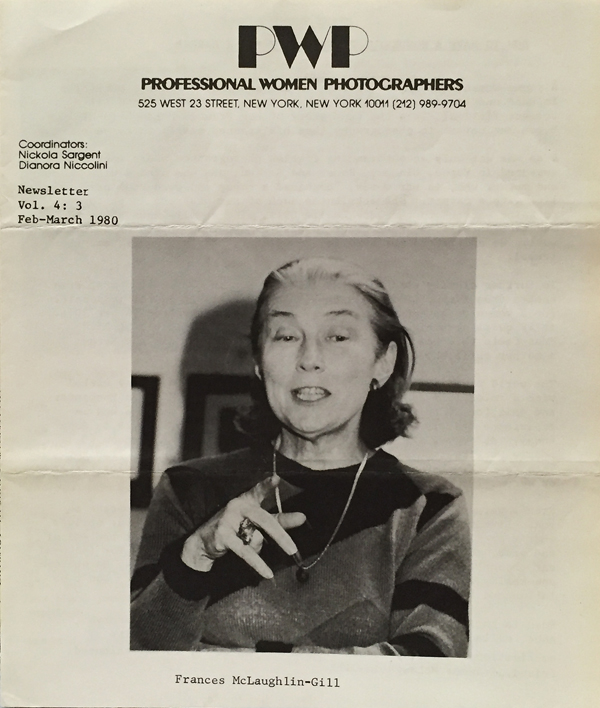

Poking around the PWP Archives, I was finally able to put a face to the mysterious name. On the front of an old newsletter where she’s featured as an upcoming speaker, Frances McLaughlin-Gill is caught in mid-gesture and speech. The image is a poor reproduction on paper yellowing with time, yet her vitality leaps out. We don’t know what she’s saying, just that she’s definite and seems about to roar, either with laughter or advice. Her work is equally alive and speaks in a visual poetry of its own. It will uplift you. Go see it.

Lives & Still Lives: Leslie Gill, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, and Their Circle curated by Elizabeth Biondi be on view through July 7th at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, 41 East 57th Street, Suite 1406.

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

BOV: The Life – An Appreciation of Dannielle Hayes

BOV: The Life - An Appreciation of Dannielle Hayes

As we know, in the beginning there was a show. Fashion Institute of Technology, 1975, Breadth of Vision: Portfolios of Women Photographers, a historic exhibition out of which PWP developed. But there was another vision going on, a life and personal outlook.

Last spring I arranged to have coffee with PWP’s founder, Dannielle Hayes. There had been talk of an oral history, work on the archives, but the meeting was left casual, the topics open.

We met at a bistro near her apartment in the East Village. With close-cropped blond hair and black frame glasses, Hayes was stylish and smart, but without the “better than€ attitude that sometimes comes with accomplished New Yorkers. A sense of warmth and humor were immediately apparent; what started as a quick cup of coffee turned into a leisurely lunch.

Right here I need to come clean: the notes I took during the first twenty minutes are lost. Okay, not really lost. Nothing ever really gets lost in the house; it just goes missing for a very long time. Let’s just say they are not presently at hand. But I had my Flip camera and halfway in, begged to record. We struck a deal: if I pointed the lens away so she wouldn’t be caught chewing, I could record sound. Here is a sampling from her amazing life.

Hayes was educated at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, and Cooper Union in New York. One of her early jobs was at Fairchild Publications where she was “illustrator and writer and photographer and chief bottle washer.€ A wide range of responsibilities helped develop a wide range of skills and contacts, as well as a broad outlook. Creativity didn’t end when the shutter snapped shut; photography didn’t exist in a vacuum.

In fact, the meetings of the Breadth of Vision photographers grew out of Hayes’ concern that the show wasn’t getting enough publicity. She instinctively knew that women had to help themselves because at the time no one else would. They launched a bootstrap campaign that included taping signs to lampposts, and awareness of the show grew.

A year later, thinking way outside the box, Hayes organized a slide show called Woman Photographs Man that was shown on the back of a truck in Rockefeller Center. This attracted attention (which she primed by reaching out to publishing contacts), and she was offered a contract by William Morrow & Co. With Hayes as author/editor, Women Photograph Men was published in 1977. It was a historic book, with 100 images of men by 70 women photographers, including Arlene Alda, Barbara Gluck, Joan Liftin, Mary Ellen Mark, Barbara Morgan, Martha Swope, and Suzanne Szasz. It also contained a half folio of color photographs, unusual for the time, and an introduction by renowned film critic Molly Haskell.

Hayes was deeply involved with the project, laying it out at William Morrow, gathering and editing the photographers’ bios, and securing the top photo printer, Morgan & Morgan. “William Morrow tried to send me to some other printers and I had to look at their work,” Hayes recalled, ”and I said no,…this is not good enough. If I’m going to put my name on this book, I really want the top printer. And I…called Barbara up, [photographer] Barbara Morgan, and said ‘look, this is really important,’ and she agreed, so it was actually Morgan [& Morgan] who printed the book.€

Along with the general pressures of publishing, there were other concerns. Was the man in Patt Blue’s picture urinating or was it a stream of sunshine? Would people be scandalized by male nudity? William Morrow’s lawyer asked Hayes to sign a liability clause stating that she, not the publisher, would be responsible in case “a little blue-haired lady from the Midwest€ sued. Hayes responded that this was exactly the sort of person who would enjoy the book most, and refused to sign. Women Photograph Men came out in the fall of 1977 to excellent reviews, including one in The New York Times. No lawsuits were ever filed. Interestingly, another book with different editors, Women See Men, was published in the same year by McGraw Hill; both books had shows at the International Center of Photography.

There was also the matter of getting a photo release from Moondog, the famous street musician who was pictured in Women Photograph Men. For many years he favored a spot on Sixth Avenue at 53rd Street, but suddenly disappeared. The publishing process went on without him, and he later resurfaced, having spent ten years composing in Germany.

Not all the women photographers who gathered at Hayes’ apartment were included in the book, so she graciously bowed out as leader of the “yet unnamed PWP,” and went on to a distinguished career as a freelance photographer, writer, illustrator, and designer. But a list of Hayes’ clients (that includes Time, Inc., The New York Times, and the National Geographic Society), or the places where she’s taught photography (Canon Creativity Workshops, Simon Fraser University, the New Jersey Institute of Technology), does not even begin to indicate the wealth and richness of her ideas or the generous way in which she sees the world.

Her outlook is truly global. She once approached J. Walter Thompson, trying to put Kodak and UNICEF together, and has worked in many countries, including South Africa, Niger, Uganda, Cameroun, Senegal, Ethiopia, Tunisia, Indonesia, Jamaica, Cuba, Peru,Venezuela, Argentina and Canada. Equally impressive is her affiliation with and work on behalf of a wide range of worthy causes, including CARE, UNICEF, the United Nations’ Women’s Conference, Helen Keller International, and the 2010 Winter Paralympic Games, of which she spoke with a special fondness. The very best way to understand Dannielle Hayes is through her photographs. On her website is a movie made of her pictures from the 2010 Winter Paralympics. As a photographer, she doesn’t flinch. She simply records, without an ounce of voyeurism, and through her perception of these athletes as beautiful, gifted and heroic, we see them that way too.

There’s a saying in the piano world “you play what you are.€ Whether you’re uptight, kind, generous or mean, it all comes out in the music you make. When you look at Dannielle Hayes’ pictures, you can tell that she is filled with grace and courage and light. Hers is a beautiful life.

Her legacy? Inspiration and kindness, determination and can do. A continuing sense of awe in the face of the world and its people, and the fates that sometimes befall them. For better or worse, organizations take after their founders. In Dannielle Hayes, PWP got lucky because she was a pretty terrific place to start. For her, breadth of vision is more than the title of a show that came and went. It is very simply a way of life.

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director