Tag Archives: Catherine Kirkpatrick

Cause, Paws & Art: Photographers Helping Animals

As the owner of Printz Photography, Lisa Prince Fishler photographs pets for a living. But she has always been moved by the plight of the many animals that are euthanized each year, and in 2010, founded HeARTs Speak, an organization dedicated to bringing artists together to save the lives of animals in need.

HeARTs Speak is unique in that it works to secure stipends and other incentives so artists can work on behalf of animal causes without consequences to their own businesses, encourages relationships with third-party partners that can provide exposure for the artists, and offers educational opportunities that use art to bridge the work of animal welfare organizations and the communities they serve.

It is a thoughtful, creative and forward-looking organization that takes into account the realistic needs of all parties. From their website it is clear they are talented, have very big hearts, and love animals. It is truly a case of someone doing what they love to change the world.

PWP: What led you to actually do something for your cause rather than just make a financial contribution? Was there a specific animal/image/moment that affected you so deeply you had to so something about it?

LPF: My personal handicap is I WANT to save the world. Especially for animals. I have always connected deeply with them and find them to be amazing beyond words on so many levels and just cannot accept the fact millions die in shelters each year. For this reason, I volunteered my services to help animals in rescues. I would walk and spend time with them, and one day started photographing them as well. I was told that my photographs helped show their character better than the snapshots the shelter/rescue staff took, and helped them find homes more quickly as a result. People who saw my photographs started inquiring about having me photograph their dogs privately, and hence, my business was born.

I always knew a lot of animals lost their lives in high intake shelters, however, it was not until I actually watched a video that showed sweet, loving, beautiful dogs and cats, led down the hall to be put to sleep that I decided I had to do more. There were rooms and garbage containers overflowing with the bodies of dogs, puppies, cats and kittens. I could not stop the video, instead, I watched through my tears and sobbing and grew determined to come up with a way to stop this insanity. I thought about how if I could afford to, I would only do the work that saves lives. I wouldn’t even think twice to choose photographing animals in shelters over private clients’ pets. This, coupled with my belief that there is power in numbers served as the catalyst for HeARTs Speak. HeARTs Speak would be a 501c3 umbrella for like-minded artists, and it would raise the funds necessary to let these artists choose to do the work that gives back to animals in need.

PWP: What are the figures like? Roughly how many animals in the United States live in shelters? Are abused? Are euthanized?

LPF: According to the Humane Society of the United States, “animal shelters care for 6-8 million dogs and cats every year in the United States, of whom approximately 3-4 million are euthanized.”

I do not believe there is a resource that keeps track of how many are abused.

PWP: On your website you speak about the conflict between photographing for pay and photographing for a cause. Can you talk a little about this issue that all photographers have to deal with? How do you draw boundaries?

LPF: Again, this is the premise upon which HeARTs Speak was founded. We have close to 400 members in 11 countries. We all provide services for no charge to help animals in shelters and rescues. I don’t think, however, there’s anything wrong with receiving compensation for doing this important work and this is something we, as an organization, are working to change this. We are working to raise the funds to provide a stipend to our members each time they go to a shelter or rescue to enable them to make the choice to help more animals, if they so desire. There are lots of people in this world that make lots of money for doing bad things. We think it’s not a lot to ask to simply make enough to sustain ourselves, doing good.

PWP: Can you tell us about a case where photographing an animal changed the life of that animal?

LPF: It happens all the time. An animal is on death row, we photograph them, and then share that image via our social network via the internet, and that animals is saved. That is what we do!

– Catherine Kirkpatrick

Rivka Katvan – An Appreciation by Harriet Whelchel

Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change –

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month.

Photographer Rivka Shifman Katvan creates diverse narratives that range from intimate backstage scenes during Broadway plays, the daily existence of eccentric Catskills villagers, the mysterious lives of mannequins reflected in store windows, and fairy tale-like scenes of Coney Island. Her work has been widely celebrated throughout New York’s artistic and theatrical communities, including Gallery 138, the International Center of Photography, the Museum of the City of New York, and the Museum of Television and Radio. She has also been featured in numerous publications in print and online, including The Guardian Weekend Magazine, The New York Times, as well as www.kodak.com and www.lanciatrendvisions.com.

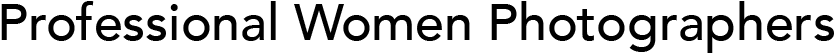

Katvan’s relationship with the theater originated in 1978 during a backstage visit to a friend who was appearing in The Magic Show. She was immediately struck by the contrast between the illusions being created onstage and the down-to-earth reality of backstage life. Katvan soon became a backstage fixture, learning how to be discreet in other people’s private spaces, putting them at ease and gaining their trust, enabling her to catch fleeting glimpses of beloved Broadway stars like Alan Cumming, Natasha Richardson, Liam Neeson, and Elizabeth Taylor.

For many years the only fine-art photographer allowed to document backstage on Broadway during the Tony Awards, Katvan developed a special bond with the theatrical community. Feeling the need to give back to those who had embraced her so wholeheartedly, she contacted the nonprofit organization Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS in the early 1990s, offering to donate photographs to a charity auction. Since then she has made the group part of her extended family, speaking out for the cause, participating in fundraising events, and commemorating many of their efforts with her camera. According to Tom Viola, executive director of Broadway Cares, Katvan’s photographs have raised more than $120,000 for the organization.

In 2006, Katvan extended her backstage photography to New York’s Sing Sing Correctional Facility, documenting inmates (many serving life sentences) as they rehearsed the play Oedipus Rex, performed over four nights. In 2011, she participated in the State Department’s Art in Embassies program, which places artists’ works in consulates and embassies around the world in an effort to show “how art can transcend national borders and build connections among peoples.€ Her lyrical scenes of Central Park covered in snow and the Brooklyn Bridge enveloped in fog presented a strong contrast with the year-round hot climate of Djibouti, Africa, where they were shown.

_________________________________

Harriet Whelchel has been an art-book editor for more than twenty-five years, first at Abrams, Inc., and most recently as senior editor at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Currently a freelance editor, she has edited and managed projects for private clients and publishing companies, including Abrams, The Metropolitan Museum, and Rizzoli New York. She is proud to have edited Rivka Katvan’s book Backstage: Broadway Behind the Curtain (Abrams, 2001).

(Rivka Shifman Katvan will be speaking about her work at Professional Women Photographers on May 8th, 6:30 – 8:30 pm, at the Metropolitan Opera Guild, 70 Lincoln Center Plaza, West 65th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. The public is welcome, $10 at the door for non-members. For more information, call 917-304-4354.)

Links to other articles in Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change:

Gigi Stoll: Inspiration All Over the World

Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Tanya Sleiman: Capturing Elusive Photographer Helen Levitt on Film

Rivka Katvan: An Appreciation by Harriet Whelchel

Tanya Sleiman: Capturing Elusive Photographer Helen Levitt on Film

Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change –

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month.

“Before street photographers took Manhattan by storm, there was Helen Levitt. An artistic pioneer and the ultimate photographer’s photographer, Levitt lived as a total enigma, determined to dodge the public eye in favor of what she loved most: poker, baseball, and, above all, capturing the city at play. 95 Lives searches for the many, colorful lives of this female pioneer and the formidable contributions she made to 20th century art and to the city that shaped her incredible body of work: New York.” (Kickstarter campaign for 95 Lives, a film about Helen Levitt by Tanya Sleiman)

“Before street photographers took Manhattan by storm, there was Helen Levitt. An artistic pioneer and the ultimate photographer’s photographer, Levitt lived as a total enigma, determined to dodge the public eye in favor of what she loved most: poker, baseball, and, above all, capturing the city at play. 95 Lives searches for the many, colorful lives of this female pioneer and the formidable contributions she made to 20th century art and to the city that shaped her incredible body of work: New York.” (Kickstarter campaign for 95 Lives, a film about Helen Levitt by Tanya Sleiman)

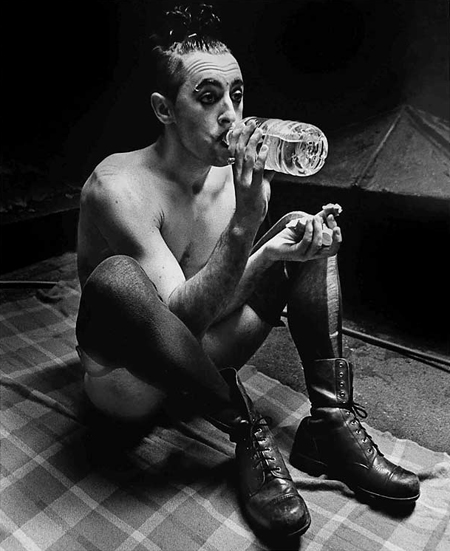

Tanya Sleiman is a documentary filmmaker with an MFA from Stanford University. She currently teaches at Diablo Valley College in California, and recently taught with NYU Tisch School of the Arts in Cuba as the 2011 on-site Program Director for documentary production.

Tanya Sleiman is a documentary filmmaker with an MFA from Stanford University. She currently teaches at Diablo Valley College in California, and recently taught with NYU Tisch School of the Arts in Cuba as the 2011 on-site Program Director for documentary production.

Sleiman’s 2008 visual essay, A Chronicle Of Concrete, was screened in international festivals and broadcast on PBS. She also produced Iraq in the USA, a vibrant collective portrait of Iraqi refugees in America. In 2008, Sleiman began examining Helen Levitt’s legacy, sharing a short film project at the Cantor Arts Center for In a New York Minute: Photographs by Helen Levitt (April, 2011). She is currently at work on a longer film about the photographer called 95 Lives.

While Sleiman calls herself an “ordinary person,” it is clear she is anything but. Here are some of her insights on Helen Levitt and changes in the field of photography since Levitt’s day.

PWP: How did you get interested in film?

Two sources were my fuel for film: Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive launched it and New York’s international and experimental scene sealed the deal. I was in my 30′s when I discovered it was for me. Earlier as an undergrad, I pursued social sciences at Berkeley, where there happened to be an amazing art house cinema space, The Pacific Film Archive. I didn’t know it was world-class then. I only knew it was another amazing resource on the campus. I went to the PFA whenever I could to watch art films as a “break€ from my social theory studies. Watching a film was always a window to another world, another set of metaphors for life. I loved it. Yet in my years of undergrad studies, I never imagined I’d be someone who would make films. I thought I’d be a diplomat or a policy maker or educator or social justice crusader. Something responsible, something that made a difference. To me, film and photography were hobbies, not professions. I didn’t take a single art history class. I took painting-for fun. Art was on the level of dance for me. Something you do to unwind and explore, not something you make to change the world. After undergrad, I moved to Damascus, Syria, to study Arabic literature and language. There, I continued to watch international cinema, with films from the Arab Middle East as well as any cinema that came to town through the cultural centers of India, Spain, and France. Still, I didn’t think I’d make or study film.

When I moved to New York City after Damascus, my free time was once again at the movies. After my attending many screenings with the artists present, I began to see that the filmmakers didn’t look too different from me. I began to think I might be able to tell stories through image and sound. In 2005, I picked up a video camera for the first time with an aim of making my own film. I didn’t have a particular story to tell; rather, I had a deep urge to learn how to make films. So I enrolled in a continuing ed class at The New School, where I worked. It was documentary production. I was familiar with still photography, but not film/video. I have zero home movies from my childhood.

With my first film, I made classic rookie mistakes, such as turning the video camera vertically to frame a shot of squirrels scampering up a tree.This was the beginning of my learning how to un-see what the human brain perceives. Of course, now smart phone cameras change aspect ratios for us as we switch our compositions! Despite my backwards composition obstacles, I had success too, and much of it was because I worked with a partner, Richard Adams. We complemented each other: what I lacked in technique, he had. I brought people skills and good interviewing style to our documentary. We both had a good eye for composition or interesting subject material. After finishing our short documentary that fall, I knew I was ready to move full time into film. I quit my education administration job, drew on personal savings, and enrolled in NYU film school’s continuing ed program to make my own films. For me, it was about documentary’s power to combine so many things I love in a dynamic way: art through the image and sound production; interacting with people; and storytelling and educational elements if you’re lucky. And no day is the same, which I love.

PWP: What led you to make a film about Helen Levitt? Was there a personal encounter or was it simply appreciation from afar?

The answer truly began with a question: how come I don’t know Helen Levitt?! How could there be nothing documenting her legacy? I didn’t know anything about Helen Levitt until the year I first studied her work. In general, I love images which capture ordinary life. Levitt’s scenes with texture in beauty and grit, humanity’s grace and awkwardness, as well as our humor and melancholy, captivated me in a master class with a curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was a week of looking at images, not making them. Each day that week, we examined an artist in depth. Masters such as Eugene Atget, August Saunder, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Walker Evans were our beginnings. With each master, I knew the artist’s biography and something about their images. Though I neither studied photo history nor photography in undergrad, I had enjoyed an entire decade of New York City’s gallery and museum scene, and I was always in the photography galleries.

However, when we got to the Helen Levitt day, I had zero information about the artist behind the images. I’d absolutely seen her images before. How come I knew nothing about the artist? How could I not know anything about a major female photographer? I asked the Met curator: which documentaries (plural) should I watch to learn more about Levitt? He told me, “no documentaries exist on Levitt.” I was shocked. I asked why. He said something about Ken Burns trying and failing. I later would learn, the curator meant Ric Burns who made a PBS series on New York and uses some of Levitt’s images in one scene and probably tried to get Levitt to participate.

With that glaring absence, that appalling lack of a film on a major artist, I was convinced I would use the opportunity of my MFA thesis film to make a modest film on Helen Levitt. She was still living that year, so I flew to New York that October to meet her. When I asked what she thought about my making a small film about her life and legacy, she said very matter-of-factly, “Wait ‘til I’m dead, hon.€

PWP: What made you go beyond appreciation to take action?

How could I not make a film? I felt I had discovered an enigmatic treasure and had to share it. The feminist in me was determined to celebrate a major female pioneer. The documentary artist in me was gripped by the images. The history lover in me could travel in time straight to the moment the images were captured. Last but not least, we live in an era where films reach audiences in ways that art monographs simply cannot. I am committed to making a lyrical film, combining the master artist’s eye and my research to share how she transformed real streets into theater. At first, I thought a modest short documentary would be a great first step. The more I researched however, the more I discovered a fascinating person whose innovative work had to be told through film.

I have been unearthing archival gems, finding hidden stories, collecting oral history, creating soundscapes and vivid scenes. I can’t wait to share the work and enjoy viewers’ own encounters with Levitt’s images.

PWP: The legacies photographers leave behind and their preservation can be troubling. Gifted people vanish without a trace as tastes change and time moves on. The work of Eugene Atget and Vivian Maier had near misses with oblivion. Why was Levitt important? What about the legacies of photographers in general?

So many stories around Levitt and her work are gripping. First, how did she choose to portray 1930s Black and Spanish Harlem life with vitality and mystery, despite American documentary’s Depression-era aesthetics? Second, in the 1950s why did she embrace color when photography’s elite thought it vulgar? Third, how did she work with motion pictures on the streets of Harlem decades before cinema verité had a name? Throughout, how did she, as a woman hold her own in a dominantly male photographers’ club, at a time when it seems it was harder than it is now? Unfortunately, it is now nearly 4 years since she died and it is very unclear how her legacy will be officially promoted and preserved. With many photographers, their work immediately increases in market value after their passing. It is not always the case that an estate is named, or that an estate is ready to work with institutions to promote archiving, preservation, organization, education, and research. The cases of Atget and Maier are great examples of the physical archive needing preservation and dissemination. With artists working now in digital realms, how will future discoveries uncover work on a floppy disk when there is no hardware to run it? I am grateful that a few centers globally are taking seriously the challenges of digital file migration, but I suspect it will be much harder in future for someone like Vivian Maier to be a discovery. Levitt will not go to the trash bins of history because she is well-chronicled within photo history. My urgency to make a film about her life and legacy is driven by the belief that Levitt’s best work is from the street. I feel deeply that it is time to remove the mystique around her process to explore her unique way of seeing because I believe it can inspire us in our current moment to look not at our handheld devices, but instead, to look up and around our world with fresh eyes.

PWP: Levitt dropped out of high school, began working for a commercial portrait photographer, and had early and direct contact with greats in the field. Can you compare her photographic education with the art/graduate school route taken by many photographers today?

With the art/grad school route, there is an overt professionalization. Artist’s statements; teaching credentials; certification of proficiency in a software, etc. A positive part of school is the production of many small projects within a short period. In Levitt’s day, there were some centers for photography, and schools of thought often emerged from like-minded artists, but the real path was master-apprentice and trial by dodging and burning.

In my opinion, the best part of current art education is when a senior artist and an emerging artist can connect and their encounter changes both parties into new creative explorations. This idealized version of the master-apprentice relationship is how Levitt learned photography. Levitt formally studied only with Jay Florian Mitchell (studio). But she trained her eye on the works of Walker Evans (Americana), Henri Cartier-Bresson (street), and painting and photography in galleries and museums in New York. She was particularly struck by a show of surrealist photo images she saw in New York at the famed Julien Levy gallery. The portfolio we know today from a professionalized program was the basic idea she had when she first called on Walker Evans. She had begun exploring image-making in New York’s streets, and she brought him a set of prints for his feedback. It was the ultimate critique session because that day Evans was there with the writer James Agee, and a new partnership began for Levitt with both artists. In Levitt’s day, it was the cost of the equipment, the transportation, and the time. Today, it’s all of those elements, plus thousands of dollars in tuition. Degrees can cost a small fortune, and not every program is worth the money. For me personally, I was very keen on earning an MFA. I like academia; I value the credential for teaching; I studied film and digital production with master documentary artists; I wanted a small seminar-style program and Stanford accepts 8 students per year to study with 3 full-time documentary production faculty as well as an entire department of art practice, art history and film theory. So in my personal case, it was a good match. However, there are plenty of paths to filmmaking outside the academy.

PWP: Over the past 30 years, there have been tremendous changes in the field of photography. What used to be largely B&W and of a relatively modest scale has become large, brightly colored, and overwhelmingly digital. There is mixed media and staged imagery. Photography has entered the art world in a big way. Can you talk about how the photographic landscape was different in Levitt’s time?

Photography was still insecure in calling itself an art form when Levitt began working in 1931 (age 18) for a commercial studio photographer in the Bronx, J. Florian Mitchell. Eugene Atget in 1890 in Paris did not self-identify as an artist. He stated simply that he was providing documents for artists, i.e., photo images for “real artists€ such as painters. When Levitt started her street photography work with a used camera, completely divergent definitions of photography were competing for attention. It’s documentary. It’s reportage. It’s surrealism. It’s pictorialism. The question Walter Benjamin articulated in 1936 concerning art in the age of mechanical reproduction haunted the first images taken by a shutter, and this certainly applied to Levitt in the studio and on the street in the 1930s.

As for the camera technology and printing techniques after she left the commerical studio, Levitt started with a Voigtlander, with which she considered a portraiture career, followed by the Leica, after encountering Henri Cartier-Bresson in person in New York at a photo salon discussion. He shared why it was his preferred camera, and it became her camera of choice thereafter. Levitt printed her 35mm images and images for Walker Evans in a kitchen darkroom, and later, she used the bathroom tub in her apartment to print her images. She printed 2×2 versions of negatives she thought were promising, in order to save paper. If an image made her cut, it was enlarged, but never larger than 8×10 for her first 5 decades of work. She began in black and white, then pioneered a humanist color slide photography of New York’s streets in the 1960s, showing her color work in the MoMA several years before William Eggleston’s seminal color show. She never worked with digital, but she did enjoy a toy camera or two!

PWP: I sense in Levitt’s work a shyness and sensitivity. What was she really like?

Levitt was absolutely shy in public and hated to give interviews. She was fiercely intelligent with a sharp gallows humor that could catch strangers off guard, but kept her friends very entertained, unless they were the subject of the joke.

When I met Levitt, she was 95, and she had better posture than I did. She was as fit as someone her age could be and sharper than many 25 year-olds I teach today. She was very sensitive to the needs of her pet Binky, who was sick that day, perhaps in solidarity with Levitt, who was ill too. I spent one day with Helen Levitt and since then, four solid years researching her life and speaking with the people who knew her best. What I’ve gathered is that she was humble, yet aware that she had made good work in photography. And that she had loyal friends in different spheres who did not intersect. What I’m hoping to do in my film is bring all these lives with whom she connected into one frame.

PWP: There is also sense a general change in the way things are. In Levitt’s time, it seemed possible to self-educate, possible for a regular person to live in Manhattan, to reach out and engage directly with luminaries in their field. Even the street life seemed different. As Levitt said herself: “Children used to be outside. Now the streets are empty. People are indoors looking at television or something.€

Certainly, the 1930′s street life was radically different. Poverty in the depression meant that people knew to upcycle, recycle, reuse, repair and reinvent. Thus, the street images Levitt captured don’t have garbage cans nor garbage strewn everywhere. Air conditioning did not exist in the 1930s when Levitt started to photograph in the streets. Summer indoors in Harlem then was sweatier than a Bikram Yoga session today. Gas lamps were transitioning into electricity, however, indoor dark apartments were not very bright nor appealing in the summer. Thus, for the people Levitt photographed, Harlem’s public streets felt fresh and breezy and vast in contrast to cramped and dark interiors in tight tenement apartments. Cars did not race down the streets every two seconds, so children could use the asphalt of the roads for their art canvases with chalk drawings covering Harlem. Glass and steel were not the dominant storefront building materials, instead brick brownstones of a human scale provided children with another canvas for their chalk drawings. All these conditions in New York allowed a rich cross section of urban denizens to pass before Levitt’s lens, and her unique way of seeing the dramas and dances of the street provide us today with a superb window on the worlds these street actors inhabited.

As for the possibility to self-educate, I truly think it is a matter of reframing how we look at ourselves and our luminaries. I am an ordinary person. I was still ordinary when I wrote Levitt a letter in 2008. When she didn’t write back, I picked up the phone and called her. I figured, she’s 95. Time is of the essence. Maybe she’s too busy or too tired to write back. I never allowed myself to feel I wasn’t worthy of the task. After all, she had a public, listed number. She was hiding in plain sight. She answered the phone. We set a date, and I showed up at her door.

I’ve done the same countless times since with her friends and curators who knew her. To interview all the folks I’ve gathered for this film project, I have had to write, call, and email some of the finest luminaries of film, photography and criticism. I don’t think my Stanford MFA is why they respond. They like Levitt’s work or they knew Levitt well, and they respect my project. They trust that we can make something richer by talking or working together.

Levitt called on Walker Evans, but she knew when she was ready to show her work. I didn’t set out to make this film when I didn’t know how to hold a camera. I worked on my skills as much as I possibly could, and I set forth. My unsolicited advice to folks: work on your craft, and you will learn by doing and failing. To find a mentor, keep calling, emailing, showing up and writing to whomever you think can open a new door. You never know what you will walk into.

If a luminary you admire is to busy for you, watch their talks on the internet while you find someone else. I know it can feel daunting at times, but in this era of the internet superhighway, and air-conditioned/heated libraries and information everywhere, self-education is absolutely possible. Don’t be overwhelmed by technical issues or shyness. Find something you want to pursue and go for it with unabashed enthusiasm.

Catherine Kirkpatrick

Archive Director

Links to other articles in Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change:

Gigi Stoll: Inspiration All Over the World

Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Tanya Sleiman: Capturing Elusive Photographer Helen Levitt on Film

Rivka Katvan: An Appreciation by Harriet Whelchel

Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change –

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month.

Today photography is a major force in the art world. Prints sell for thousands of dollars, and photographers like Cindy Sherman and Annie Leibovitz are global names. But there was a time, not too long ago, when things were different. In the 1960s and 70s, very few galleries featured photography. Print prices were low, and opportunities for photographers were extremely limited.

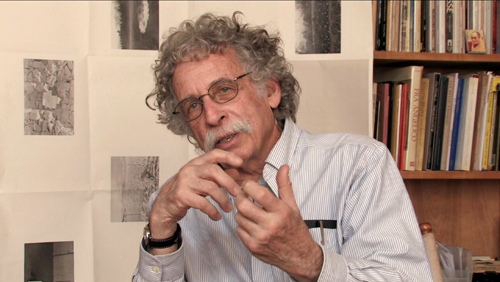

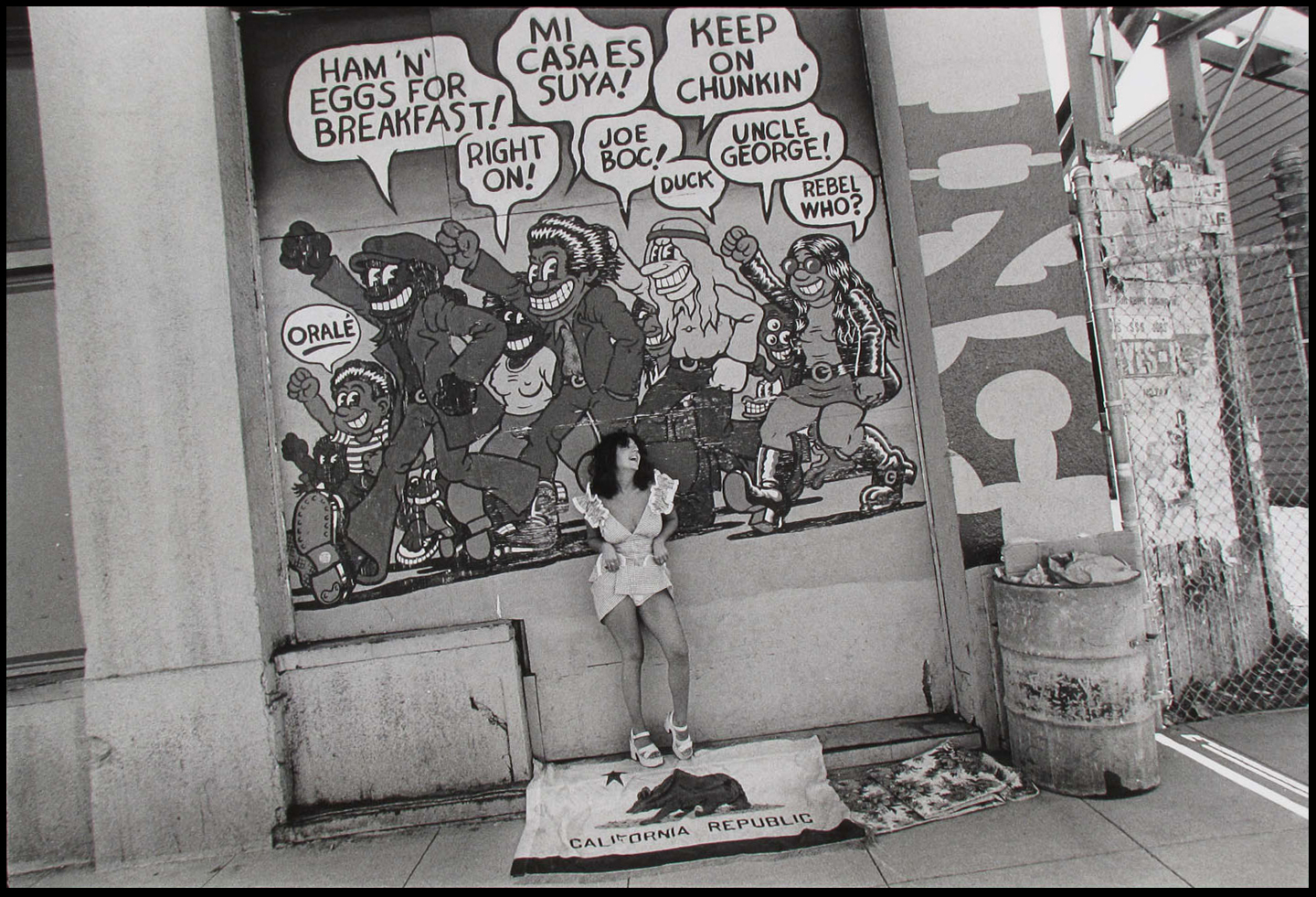

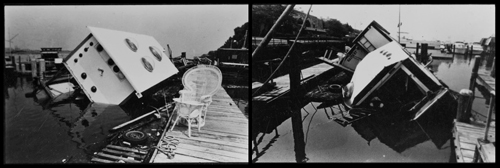

In 1969, a dynamo named Maggie Sherwood bought an old houseboat in Ocean City, Maryland, and created the Floating Foundation of Photography. Moored along Manhattan’s West Side and at various points along the Hudson, the little purple boat became a school, gallery, and gathering place for many photographers of the day. Sherwood taught classes at Sing Sing Prison (along with luminaries like Lisette Model and Eva Rubinstein), and organized al fresco shows on the New York City piers and in Central Park.

Not only did she embody the free-spirit of the 1960s and 70s, but anticipated many trends in the photographic field. She did mixed media before it was fashionable, experimented with pinhole and Diana cameras, and single-handedly engineered a social network for photographers in a day before the Internet. In 1984, Maggie Sherwood passed away from cancer, and in 1986 the boat was sold, though the Foundation lives on through the efforts of her son, Steve Schoen, and her daughter-in-law, Jone Miller.

In 2009, Beth E. Wilson curated a landmark show on Sherwood at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art. Wilson is an art historian, critic, and curator, with a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy from Georgetown Univeristy, and graduate degrees in Art History from Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center, where she is completing a dissertation on the World War II work of photographer Lee Miller. She regularly teaches History of Photography, History of Film, and courses in late 19th and early 20th century art at SUNY New Paltz. Here is a conversation with her.

PWP: How did you discover Maggie Sherwood and the Floating Foundation of Photography, and what struck you most about her and the foundation?

As art critic for the Hudson Valley magazine Chronogram, I first encountered Maggie’s work in a small show organized by her son and daughter-in-law, Steve Schoen and Jone Miller, who now live in the Hudson Valley. Maggie’s work struck me as a playful, creative take on New York City in that particular time frame (mid-60s to mid-80s). Getting to know Steve and Jone was a tremendous education in itself, as they told me the whole story of how Maggie had bought the houseboat almost on a whim, and turned it into a sort of clubhouse/exhibition space for her photographer friends (including luminaries like W. Eugene Smith and Lisette Model, among others), and how Steve had developed the FFP’s photo-based education program, taking them to Sing Sing and beyond. This story seemed to be a gift that kept on giving.

PWP: Why is she important and what is her legacy today?

The whole phenomenon of Maggie (that term captures her personality particularly well) and the boat is something that obviously was terrifically important and influential on the photographers who were pulled into her orbit at the time, something that became very apparent to me as I worked on the exhibition and contacted a number of them. The sad part is that so many of these talented people have largely drifted apart since, and the story of the boat has gradually been fading away over time–something that I hope the exhibition (and now the catalogue) have done something to redress. The show became something of a little reunion for many of the photographers in it.

We sent copies of the catalogue to a number of institutions and individuals when it came out, prompting a lovely little note from Malcolm Daniels at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, thanking me for bringing to his attention a piece of New York photographic history that he hadn’t previously known about. So the question of Maggie’s legacy is something of an ongoing proposition, and still I think very unsettled. I would love to see her work, and the work of the Floating Foundation to be more widely known.

PWP: Sherwood seemed to create a social network for photographers in a time before the Internet. How did she manage to do this and what did she enable other photographers to do?

The FFP happened at a time when people still had to make the effort to get together face-to-face–you couldn’t just dial up your Facebook newsfeed to find out what was going on. Photography itself was still a very material practice, all chemistry and paper and darkrooms and film, which basically demanded that people spend some time together, looking at prints, critiquing each others’ work, etc. Maggie came of age as a serious photographer in the workshops conducted by David Vestal, in which he scrutinized the students’ prints within an inch of their lives (and he regularly registered his displeasure with any number of Maggie’s unorthodox experiments). You can’t quite do that sort of thing by swapping jpegs back and forth. The analogue basis of the medium at that time, I think, sort of demanded something like the ‘clubhouse’ environment provided by the boat.

At a time when the opportunities for gallery exhibitions of photography were very limited, the chance to show on the boat, embedded as it was in a significant matrix of practicing photographers, must have been absolutely invaluable, especially for younger, developing artists. And then with the development of the community and institutional education programs, the FFP made photography an effective means of bringing people together, and to enable them to examine and to share their own experiences. The idea that the inmates at Sing Sing were permitted to carry cameras around with them to shoot throughout the prison during the hours of the workshops–today that seems absolutely unimaginable. Take a look at the books published out of the FFP prison programs, and you see a much more revealing, honest account of the boredom, frustrations, and realities of life behind bars than would ever be allowed to exist today. Maggie and the FFP were all about putting these tools in the hands of those whose stories we might otherwise never know about, using photography to empower some of the most disempowered people in our society.

PWP: In the 1960s and 70s, there was a grassroots movement in photography. Individuals jumped in and got things done. Institutions like ICP, FFP, Visual Studies Workshop, PWP and Soho Photo Gallery were founded. Can you talk about what the needs were at the time and how people and organizations moved photography forward?

This was a scene that transcended just the question of photography. At a panel discussion we organized in conjunction with the exhibition, Bob D’Alessandro told a great story about how one day on the boat, a radio was playing Dylan’s “Lay, Lady, Lay€, and Maggie started dancing around to it, energetically announcing to everyone within earshot how much she loved “that Bobby Dylan.€ Next thing you know, a guy tumbled out of a hammock onto the deck of the boat in surprise–and it was Bob Dylan himself!

The whole ethos, the whole aesthetic of what went on there had everything to do with what was happening in the world at the time. The bottom-up organizing that characterized the start of organizations like ICP, the Center for Photography at Woodstock, and the other places you mention was very much of a piece with the times, especially necessary since there was no real ‘photography market’ to speak of at the time. If you took photography seriously, you had to work to erect your own support system to make it happen, to form the communities of photographers, critics, etc. that could ‘make it real’ and to recognize its intrinsic value. There are obvious parallels from that time in the development of the women’s movement, when women needed to start their own organizations to make their concerns ‘real’ to the rest of society.

PWP: Looking at the SUNY FFP catalog, I see work that is mostly B&W and of a smaller size than is fashionable today. I see exhibition venues like the New York City piers that are way more relaxed and accessible than Chelsea galleries, where you could pick up a Eugene Smith print for $50. Obviously photography has changed greatly since Maggie Sherwood’s time. Can you talk about what has been gained and what has been lost?

The meteoric rise of the photography market, mostly since the late 70s/early 80s, has completely changed the landscape. Back in the day, when prints sold relatively cheaply, nobody could afford to make huge prints. Now the market seems to provide the most authoritative validation of a photographer’s work, and as a result, serious discussion of aesthetics and so on functions largely as ‘shop talk’ between photographers, who often produce enormous prints in response to the market demand. And don’t get me started on the diminished importance of criticism itself. I think when a beautifully, painstakingly produced print like Gene Smith’s Mad Eyes could be sold for a relative song, its value resided primarily in its intrinsic qualities, its aesthetic and its documentary function. Nowadays, most of that is trumped by its potential auction price.

The upside of this is that (at least for some photographers) it is possible to earn a living, to have a career doing one’s photography–I’m sure Smith wouldn’t have complained if he could have realized more income by selling his prints. And with the growth of the market, the audience for photography has grown as well, so there are many many more people out there who pay attention to it, attend exhibitions, etc., although I wonder sometimes how divided that attention might be, especially as the media tend to flog the astronomic prices achieved by individual prints at auction. There’s a point at which market value becomes overbearing, so we’re put in that special hell of “knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing,€ to quote Oscar Wilde.

I think that back in the 60s and 70s, there was a palpable sense of people coming together to say meaningful things about their community/society/world, and a fundamental belief that photography could provide a truly accessible way into all that. It’s not just a question of the photographers, but also a radical opening to potential audiences, as exemplified by the FFP-organized show The People, Yes! that was held in Central Park, which was subsequently packed up and shown in a public square in Mexico City. This was a time when photography could be by, about, and for the people, in a broad sense, with hundreds of photographs simply mounted between pieces of plexi and hung on open-air stands in the middle of the park–obviously something you wouldn’t do with high market-value prints. I suppose the closest we get to that today is Flickr, but somehow that doesn’t bottle the same lightning. My archival/curatorial experience of Maggie Sherwood and the Floating Foundation brings me to ask questions that have more to do with ethics than aesthetics: How do we create contexts for work and for images that don’t simply reinforce the dictates of the market? What would photography by/for the 99% look like?

Professional Women Photographers wishes to extend special thanks to Steve Schoen and Jone Miller, Neal Slavin, Bob D’Alessandro, and Darleen Rubin for their help and permissions to use their wonderful images in this post.

Catherine Kirkpatrick

Archive Director

Links to other articles in Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change:

Gigi Stoll: Inspiration All Over the World

Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Tanya Sleiman: Capturing Elusive Photographer Helen Levitt on Film

Gigi Stoll: Inspiration All Over the World

Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month

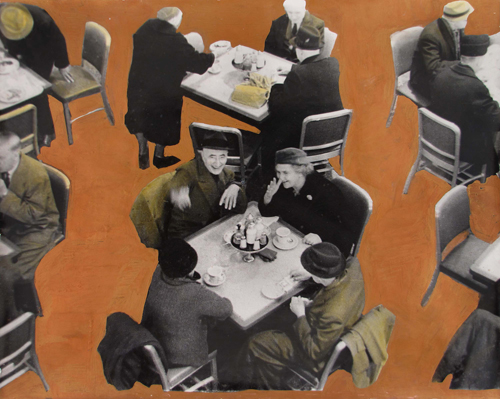

Gigi Stoll began photography while working as a fashion model, using a Polaroid camera to snap pictures of friends. After covering the Leu Family Iron at a tattoo convention in Amsterdam, her images were featured in a gallery on New York’s Upper East Side, and a new career was off and running. Stoll’s work has been featured in British Vogue, French Vogue, Japanese Vogue, Harpers Bazaar, Vanity Fair, W Magazine, GQ Japan, Instyle, Visionaire, V Magazine, VMan. She has also worked for Orient-Express Hotels Ltd. to document their corporate social responsibility projects, and for 100cameras.org, in which Leica Cameras sponsored her trip to India and the Russ Foundation. These missions have taken her all over the world, allowing her to experience many different cultures and ways of life. (All the images in this article are ©Gigi Stoll)

PWP: You speak with great emotion about your humanitarian work. Why it is so important to you?

GS: In 2008, I began documenting a pediatric medical mission. They do one mission a year and the doctors/staff volunteer their time. I learned that if one image can bring awareness and help change a child’s life, it is worth everything. After six medical missions, I am addicted. The doctors are the real artists, I just document their work. This led to other clients who saw my images published online and hired me for different humanitarian assignments. I love all the travel and adventure.

PWP: What made you take action as opposed to making a donation?

GS: In 2008, I was returning to NYC after traveling in the Sahara Desert, Morocco and I began one of those long layover conversations with a woman in Casablanca Airport. She was returning to New York on the same flight. She told me she was involved with a group of doctors who wanted to start a pediatric medical mission and they were looking for a photographer. I became official photographer in 2008 with ISMS Operation Kids. I have since traveled once a year to document their work. We have gone to Morocco, Peru, Egypt, and Kenya twice. On March 7th we will go to Guatemala. My work is used for promotions, fundraisers and websites.

PWP: What was your most rewarding experience?

GS: My recent assignment to Myanmar for the Orient-Express Hotels Ltd. I was hired to document their CSR Projects (clinics, orphanages, schools, etc.) We are still going through the final edits. I get to relive the experience each time I edit the images. I fell in love with the people, the children, the temples, the food, the landscape and getting lost in Yangon. A fascinating destination. It was a dream job.

PWP: In many cases, those actively engaged in a cause find that it opens new, often unexpected horizons. How has your humanitarian work enriched you as a person and changed your photography?

GS: It has changed my perspective in a broader sense, by allowing me to experience different worlds and cultures, and by affecting change and/or bringing awareness with photography to people in need. I shipped two 20 pound boxes to India/Russ Foundation this week full of donated shoes, clothes, school books, rain gear, etc.

Student/Nallamani High School – Madurai, India 2012 (100cameras.org/Russ Foundation) Sponsored by Leica Cameras

There are so many ways to help. I really enjoyed the book Half The Sky-it knocked me on my feet to get involved however I could. I micro fund two women in Kenya through Kiva.org. And I love Heifer International. I grew up on a farm in Texas and being able to buy a family a goat or chicken can really change their lives for the better. There is alot of inspiration out there. You just have to look for it.

Catherine Kirkpatrick

Archives Director

Links to other articles in Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change:

Gigi Stoll: Inspiration All Over the World

Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Tanya Sleiman: Capturing Elusive Photographer Helen Levitt on Film