Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change –

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month.

Today photography is a major force in the art world. Prints sell for thousands of dollars, and photographers like Cindy Sherman and Annie Leibovitz are global names. But there was a time, not too long ago, when things were different. In the 1960s and 70s, very few galleries featured photography. Print prices were low, and opportunities for photographers were extremely limited.

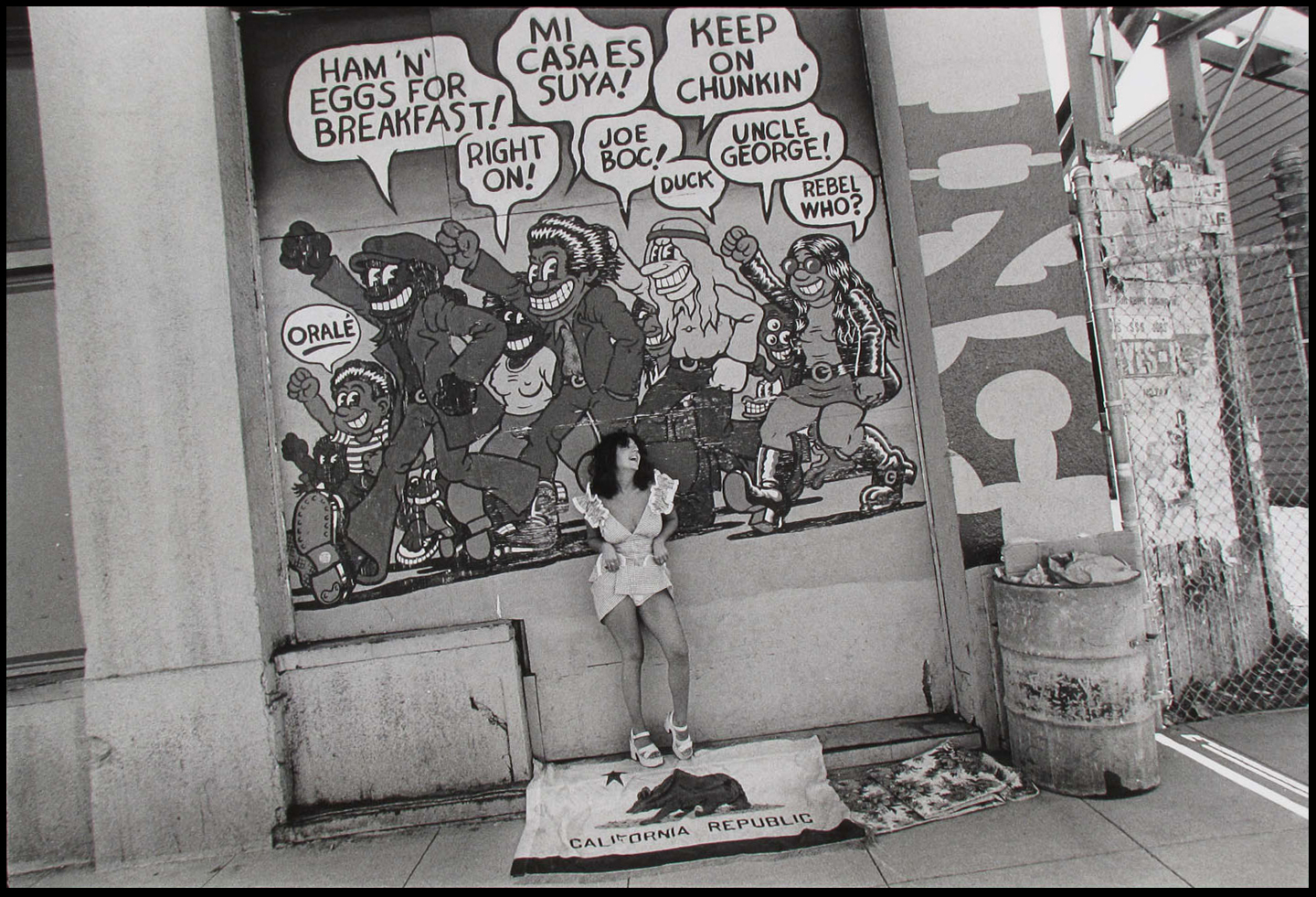

In 1969, a dynamo named Maggie Sherwood bought an old houseboat in Ocean City, Maryland, and created the Floating Foundation of Photography. Moored along Manhattan’s West Side and at various points along the Hudson, the little purple boat became a school, gallery, and gathering place for many photographers of the day. Sherwood taught classes at Sing Sing Prison (along with luminaries like Lisette Model and Eva Rubinstein), and organized al fresco shows on the New York City piers and in Central Park.

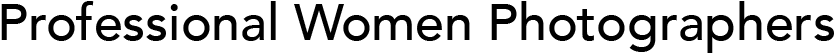

Not only did she embody the free-spirit of the 1960s and 70s, but anticipated many trends in the photographic field. She did mixed media before it was fashionable, experimented with pinhole and Diana cameras, and single-handedly engineered a social network for photographers in a day before the Internet. In 1984, Maggie Sherwood passed away from cancer, and in 1986 the boat was sold, though the Foundation lives on through the efforts of her son, Steve Schoen, and her daughter-in-law, Jone Miller.

In 2009, Beth E. Wilson curated a landmark show on Sherwood at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art. Wilson is an art historian, critic, and curator, with a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy from Georgetown Univeristy, and graduate degrees in Art History from Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center, where she is completing a dissertation on the World War II work of photographer Lee Miller. She regularly teaches History of Photography, History of Film, and courses in late 19th and early 20th century art at SUNY New Paltz. Here is a conversation with her.

PWP: How did you discover Maggie Sherwood and the Floating Foundation of Photography, and what struck you most about her and the foundation?

As art critic for the Hudson Valley magazine Chronogram, I first encountered Maggie’s work in a small show organized by her son and daughter-in-law, Steve Schoen and Jone Miller, who now live in the Hudson Valley. Maggie’s work struck me as a playful, creative take on New York City in that particular time frame (mid-60s to mid-80s). Getting to know Steve and Jone was a tremendous education in itself, as they told me the whole story of how Maggie had bought the houseboat almost on a whim, and turned it into a sort of clubhouse/exhibition space for her photographer friends (including luminaries like W. Eugene Smith and Lisette Model, among others), and how Steve had developed the FFP’s photo-based education program, taking them to Sing Sing and beyond. This story seemed to be a gift that kept on giving.

PWP: Why is she important and what is her legacy today?

The whole phenomenon of Maggie (that term captures her personality particularly well) and the boat is something that obviously was terrifically important and influential on the photographers who were pulled into her orbit at the time, something that became very apparent to me as I worked on the exhibition and contacted a number of them. The sad part is that so many of these talented people have largely drifted apart since, and the story of the boat has gradually been fading away over time–something that I hope the exhibition (and now the catalogue) have done something to redress. The show became something of a little reunion for many of the photographers in it.

We sent copies of the catalogue to a number of institutions and individuals when it came out, prompting a lovely little note from Malcolm Daniels at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, thanking me for bringing to his attention a piece of New York photographic history that he hadn’t previously known about. So the question of Maggie’s legacy is something of an ongoing proposition, and still I think very unsettled. I would love to see her work, and the work of the Floating Foundation to be more widely known.

PWP: Sherwood seemed to create a social network for photographers in a time before the Internet. How did she manage to do this and what did she enable other photographers to do?

The FFP happened at a time when people still had to make the effort to get together face-to-face–you couldn’t just dial up your Facebook newsfeed to find out what was going on. Photography itself was still a very material practice, all chemistry and paper and darkrooms and film, which basically demanded that people spend some time together, looking at prints, critiquing each others’ work, etc. Maggie came of age as a serious photographer in the workshops conducted by David Vestal, in which he scrutinized the students’ prints within an inch of their lives (and he regularly registered his displeasure with any number of Maggie’s unorthodox experiments). You can’t quite do that sort of thing by swapping jpegs back and forth. The analogue basis of the medium at that time, I think, sort of demanded something like the ‘clubhouse’ environment provided by the boat.

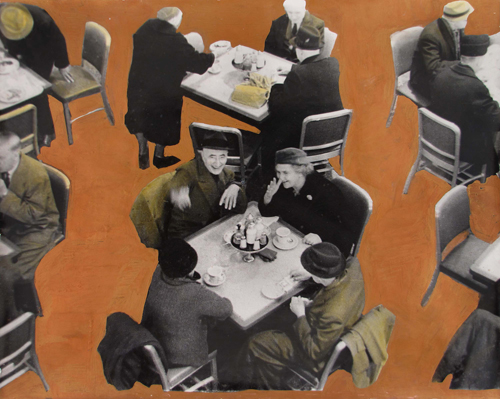

At a time when the opportunities for gallery exhibitions of photography were very limited, the chance to show on the boat, embedded as it was in a significant matrix of practicing photographers, must have been absolutely invaluable, especially for younger, developing artists. And then with the development of the community and institutional education programs, the FFP made photography an effective means of bringing people together, and to enable them to examine and to share their own experiences. The idea that the inmates at Sing Sing were permitted to carry cameras around with them to shoot throughout the prison during the hours of the workshops–today that seems absolutely unimaginable. Take a look at the books published out of the FFP prison programs, and you see a much more revealing, honest account of the boredom, frustrations, and realities of life behind bars than would ever be allowed to exist today. Maggie and the FFP were all about putting these tools in the hands of those whose stories we might otherwise never know about, using photography to empower some of the most disempowered people in our society.

PWP: In the 1960s and 70s, there was a grassroots movement in photography. Individuals jumped in and got things done. Institutions like ICP, FFP, Visual Studies Workshop, PWP and Soho Photo Gallery were founded. Can you talk about what the needs were at the time and how people and organizations moved photography forward?

This was a scene that transcended just the question of photography. At a panel discussion we organized in conjunction with the exhibition, Bob D’Alessandro told a great story about how one day on the boat, a radio was playing Dylan’s “Lay, Lady, Lay€, and Maggie started dancing around to it, energetically announcing to everyone within earshot how much she loved “that Bobby Dylan.€ Next thing you know, a guy tumbled out of a hammock onto the deck of the boat in surprise–and it was Bob Dylan himself!

The whole ethos, the whole aesthetic of what went on there had everything to do with what was happening in the world at the time. The bottom-up organizing that characterized the start of organizations like ICP, the Center for Photography at Woodstock, and the other places you mention was very much of a piece with the times, especially necessary since there was no real ‘photography market’ to speak of at the time. If you took photography seriously, you had to work to erect your own support system to make it happen, to form the communities of photographers, critics, etc. that could ‘make it real’ and to recognize its intrinsic value. There are obvious parallels from that time in the development of the women’s movement, when women needed to start their own organizations to make their concerns ‘real’ to the rest of society.

PWP: Looking at the SUNY FFP catalog, I see work that is mostly B&W and of a smaller size than is fashionable today. I see exhibition venues like the New York City piers that are way more relaxed and accessible than Chelsea galleries, where you could pick up a Eugene Smith print for $50. Obviously photography has changed greatly since Maggie Sherwood’s time. Can you talk about what has been gained and what has been lost?

The meteoric rise of the photography market, mostly since the late 70s/early 80s, has completely changed the landscape. Back in the day, when prints sold relatively cheaply, nobody could afford to make huge prints. Now the market seems to provide the most authoritative validation of a photographer’s work, and as a result, serious discussion of aesthetics and so on functions largely as ‘shop talk’ between photographers, who often produce enormous prints in response to the market demand. And don’t get me started on the diminished importance of criticism itself. I think when a beautifully, painstakingly produced print like Gene Smith’s Mad Eyes could be sold for a relative song, its value resided primarily in its intrinsic qualities, its aesthetic and its documentary function. Nowadays, most of that is trumped by its potential auction price.

The upside of this is that (at least for some photographers) it is possible to earn a living, to have a career doing one’s photography–I’m sure Smith wouldn’t have complained if he could have realized more income by selling his prints. And with the growth of the market, the audience for photography has grown as well, so there are many many more people out there who pay attention to it, attend exhibitions, etc., although I wonder sometimes how divided that attention might be, especially as the media tend to flog the astronomic prices achieved by individual prints at auction. There’s a point at which market value becomes overbearing, so we’re put in that special hell of “knowing the price of everything but the value of nothing,€ to quote Oscar Wilde.

I think that back in the 60s and 70s, there was a palpable sense of people coming together to say meaningful things about their community/society/world, and a fundamental belief that photography could provide a truly accessible way into all that. It’s not just a question of the photographers, but also a radical opening to potential audiences, as exemplified by the FFP-organized show The People, Yes! that was held in Central Park, which was subsequently packed up and shown in a public square in Mexico City. This was a time when photography could be by, about, and for the people, in a broad sense, with hundreds of photographs simply mounted between pieces of plexi and hung on open-air stands in the middle of the park–obviously something you wouldn’t do with high market-value prints. I suppose the closest we get to that today is Flickr, but somehow that doesn’t bottle the same lightning. My archival/curatorial experience of Maggie Sherwood and the Floating Foundation brings me to ask questions that have more to do with ethics than aesthetics: How do we create contexts for work and for images that don’t simply reinforce the dictates of the market? What would photography by/for the 99% look like?

Professional Women Photographers wishes to extend special thanks to Steve Schoen and Jone Miller, Neal Slavin, Bob D’Alessandro, and Darleen Rubin for their help and permissions to use their wonderful images in this post.

Catherine Kirkpatrick

Archive Director

Links to other articles in Through a Lens Brightly: Women, Photography & Change:

Gigi Stoll: Inspiration All Over the World

Of Her Time & Way Ahead: Beth Wilson on Maggie Sherwood

Tanya Sleiman: Capturing Elusive Photographer Helen Levitt on Film