Dark Legacy, Points of Light: Photographers and Newtown Creek

Once it was an American Eden. Fish swam in its waters, animals and Indians lived along its shores. It was longer then, wider too. Most of all it, was clean.

But where water flows, industry follows, and by the late 1800s, Newtown Creek, the 3.8 mile channel* dividing western Brooklyn from western Queens, was lined with chemical plants, glue and fertilizer factories, fat renderers, and refineries to process oil. In an unregulated age, companies were free to dispose of their byproducts, including lead, cadmium, and sulfuric acid, in the waters of the Creek, which was also an outlet for raw sewage.

After World War II, manufacturing began to migrate south and overseas, leaving behind a complex and brutal legacy of contamination and ruin. In 1978, a Coast Guard patrol spotted oil streaming into the Creek near Meeker Avenue, the result of an underground spill larger than the 1989 Exxon Valdez catastrophe in Alaska. In 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency declared Newtown Creek a Super Fund site.

But this isn’t a blog about “hot spots” at Phelps Dodge, or the night soil boat of the 1800s, or the oil spill under Greenpoint that’s still going on. It’s not about history, industry or ecology, maybe not even about photography. It’s about how things start and how they end, and how they carry on sometimes in strange, unexpected ways. And about a small body of water that puts a spell over people with cameras.

Maybe this is where I should come clean: I too have a jones for the Creek. From June 5th, 2001, when my mother died, I took care of my father who had a heart attack and stroke that very day. I went from having a life, albeit a busy and struggling one, to the intricacies of elder care. It was the best thing I ever did, but also the hardest and most lonely. Wandering from time to time along the Creek or over it via the Pulaski Bridge with my camera, I found a measure of peace, and ample space in which to wander and think. For a short time, I was free.

Some years later, after my father died, I signed up for a boat tour of Newtown, curious to learn about strange-sounding places like English Kills and Whale Creek, and witness scenery compared in hushed tones to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Yet as the boat turned in from the East River, I was disappointed. The light was flat and dull, the scenery anything but mysterious.

Yet to go deeper into the Creek is to drift slowly and steadily into another world. The water, dark below with oil and filth, is streaked above with bright reflections of clouds and sky. As the land glides slowly and hypnotically by, the busy realm of the city falls further and further behind, giving way to a strange and lonely splendor of dirt roads, rocks and scrub. Every now and again, a strange, man-made confabulation rises up out of nowhere-an oddly turreted factory, a crumbling warehouse, a water treatment plant with domes reminiscent of a Russian Orthodox cathedral. Then it passes and the land slips back into barren splendor till the next structure rises, then too is suddenly gone.

Yet to go deeper into the Creek is to drift slowly and steadily into another world. The water, dark below with oil and filth, is streaked above with bright reflections of clouds and sky. As the land glides slowly and hypnotically by, the busy realm of the city falls further and further behind, giving way to a strange and lonely splendor of dirt roads, rocks and scrub. Every now and again, a strange, man-made confabulation rises up out of nowhere-an oddly turreted factory, a crumbling warehouse, a water treatment plant with domes reminiscent of a Russian Orthodox cathedral. Then it passes and the land slips back into barren splendor till the next structure rises, then too is suddenly gone.

Bridges drift overhead-the Pulaski, the Greenpoint Avenue, the Kosciuszko; time shifts downward to a slower gear, then settles comfortably into a warp. The water reflects the sky and shore till they flow together as one. Occasionally some small flurry of activity on the bank draws attention-a beer truck pulling out of a lot, a cement mixer turning its tail out over the water, a cluster of people huddled together in conversation-snippets of action, mysterious, incomplete. A spell has slipped down and pulled you into its thrall.

Then the boat stopped. The sun got hotter; I grew impatient. What was going on? Didn’t they know that people who live in New York, the real New York, had things to do?

For people of a certain borough, their twenty-four mile home is the center of the universe. There is Manhattan Island, and everywhere else, and everywhere else doesn’t count. Manhattanites are opinionated, we are pushy, but most of all, we are fast. Nothing can ever slow down because we have so many things to do, all of them important and essential. I began to fret. What was taking so long?

Then two kayakers appeared off to the side of the boat and arranged themselves in parallel formation, and a few people gathered on the Brooklyn bank, looking out onto the water.

and arranged themselves in parallel formation, and a few people gathered on the Brooklyn bank, looking out onto the water.

A voice came over the loud speaker and began to talk about a man called Bernard Ente, a photographer who had passed away at fifty-nine. It spoke about his wife and daughter, and his many friends, and my eyes shifted back to the people on the shore. I thought of my own father and stood down from my impatience.

A wreath was brought forward and lowered gently over the side. It settled, for a moment hovering near. More words were spoken, then the boat started up, and the flowers began their journey, drifting slowly away toward the line where sky and water meet, bringing to mind the words on a poet’s tombstone: “called back.€

Bernard Ente was a professional photographer and rail enthusiast, one of the founders of the Newtown Creek Alliance, an organization dedicated to rehabilitating the Creek and making it accessible for all New Yorkers. A few clicks of the mouse turned up all kinds of fond remembrances of him by all sorts of people, as well as many beautiful images he gave to waterfront organizations to further their cause.

How many people have anyone, let alone a boatload of people, honor them and their work when they’re gone? This was a man who used his art to enhance the lives and environment not only of a few, but an entire city; one photographer who stood up and made a difference. In a world full of careless images, his mattered.

_______________________________

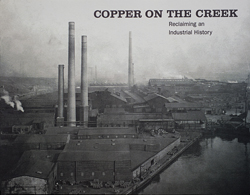

Curtis Cravens earned an MFA in photography from the University of New Mexico, then moved to New York in the 1980s to create art that focused on disused, unseen parts of the city, especially the waterfront. When a friend snuck him into the Laurel Hill Works, a former chemical plant and refinery near the Kosciuszko, he became obsessed. He photographed the site extensively, cataloging pictures and records he came across. He researched corporate archives, and tracked down former managers and workers, including the widow of a man whose name he found in a hard hat.

As the project grew, so did the questions Cravens asked himself. He wondered about the troubled history of industrial sites, and whether such places could ever be restored for use. “Art became a barrier,” he said, “in the deeper engagement with reclamation…I felt compelled to do.”

Realizing that change required a different approach, Cravens began to learn about community and environmental redevelopment. He joined the management team of the Greenpoint Manufacturing and Design Center, an old mill building at the mouth of the Creek, now home to a number of small artisanal businesses. He also wrote Copper on the Creek, a history of the Laurel Hill Works, and is currently an Economic Development Specialist for New York State.

Ever creative, he thinks of himself as a “social entrepreneur” who builds partnerships between nonprofits and government agencies, and has come to enjoy the elements of collaboration not present in the solitary pursuit of art. An unusual and productive journey from a chance encounter on the Creek.

_______________________________

Though he grew up in San Francisco and lives in the Gowanus section of Brooklyn, no one has a greater feel for the bleak, post-industrial landscape than Nathan Kensinger. A graduate of Hampshire College, his work has appeared in numerous publications, including the New York Times, as well as many galleries and museums. He is currently Director of Programming for the Brooklyn Film Festival.

Despite a background in journalism and documentary film, Kensinger admits he has “never been interested in merely reporting the straight facts of a story,” searching instead for a “more evocative portrait.” The result is a unique blending of inner and outer terrain; a deeply saturated, intensely personal “poetic reality,” one that always leaves space for the viewer’s own thoughts.

His photographs are quietly stunning but rarely simple, with details arranged to draw the eye from foreground to background, inviting the viewer into the picture to more fully contemplate the scene. Even without people, they are Brueghel-like, with many planes and intricacies; the world as we know it, but rounded and seen through a wider, darker lens. There is mystery and richness to them; they make you think.

Each of the Newtown photographers has a deep bond with the area: they are concerned with its fate and the fate of the city itself. It provokes them to action, and makes them reflect on the larger state of things. As Kensinger says:

“In many ways, New York is a…microcosm of all our country’s problems, conflicts, and social collisions. I often find myself asking, while photographing, ‘What does it mean for this country if its greatest city houses so many neglected and forgotten areas, filled with massive amounts of pollution, intense poverty, abandoned buildings, gang warfare, and post-industrial decay?’ During these dark economic times, I fear that we are nearing the end of the Empire State and of the American empire.”

Yet he and fellow artists, Laura Chipley and Sarah Nelson Wright, have forged ahead with a project called the Newtown Creek Armada. Beginning September 8th, visitors to the Newtown Creek Nature Walk in Greenpoint will be able to guide small artist-created, radio-controlled boats along the Creek’s surface while a camera records each journey underneath. The footage, to be shown later at a gallery, will give visitors “a chance to virtually immerse themselves in the toxic waters,” illustrating the pollution, but empowering them too, even if in a slightly whimsical way.

_______________________________

The great wonder of Newtown Creek is that it can generate so many ideas and journeys, one flowing into the next like notes of a song. There are others, equally compelling, the question remaining as to how a small, dirty body of water manages to exact such a measure of devotion from its fans. The Creek itself just rolls on, strange, alluring and anoxic, with all of its stories and pictures past, present, and still to come.

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director

Professional Women Photographers wishes to thank Kate Zidar, President of the Newtown Creek Alliance, and its historian, Mitch Waxman (also writer of the Newtown Pentacle blog), for their help with background information. Thanks also to the wonderful photographers who shared their stories, pictures and spirit.

*The length of Newtown Creek is sometimes given as 3.5 miles and sometimes 3.8 miles. I used 3.8 mile figure that appears on the Environmental Protection Agency’s website.