Tag Archives: 1970s

Card & Letters: A Closer Look

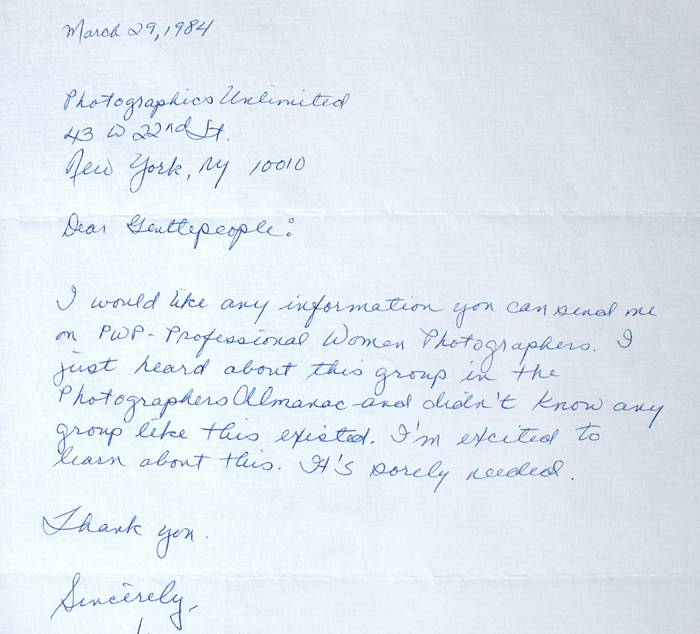

In honor of Women’s History Month, we are updating a post from a few years back that looked at the requests for information about PWP that came from women in the 1970s and 80s. If you read these letters closely, you get a sense of the isolation they felt in what had been a male-dominated profession.

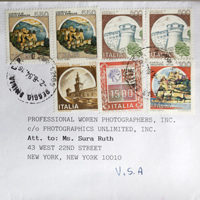

In the archives of Professional Women Photographers, there is a file of letters from women in the late 1970s and 1980s seeking information about the organization. They came from all over, from Illinois, Arkansas, Texas, even Italy. Some were handwritten, others were typed. Because there was no email, they were all on paper–notebook sheets, cheap postcards, fine bond. All wanted the same thing: information on Professional Women Photographers! They were eager to learn about and join an organization of women photographers–a novelty at the time, in a time that was not so very long ago.

Reading between lines that were handwritten or typed (on a typewriter!), you get a very strong sense of how things were for women in the field, or those trying to enter the field, in the 1970s and 80s. There have always been women in photography, but most women never regarded it as a viable career. When they did, they very often found themselves the sole female photographer in their geographic area, or were actively discouraged by men established in the field. They were desperate for a support network for projects and careers, an embracing sympathy that only comes from those who are going through the same thing.

“I read about your organization…

“Didn’t know any group like this existed…

“Though I have belonged to any number of professional organizations I have never belonged to one that treated women as equals with men photographers…As a creative professional I am especially needful of a supportive group…”

In the 1970s, when PWP was founded, there was an excitement and energy in the air. Cultural movements that began in the 60s–desegregation and women’s liberation–were coming to fruition. They weren’t just ideas anymore, they were becoming realities. Colleges were integrating and going co-ed. Women were leaving the kitchen for the corporation, and entering professions that had long been off limits or male-dominated. There was a spirit of “can do” and “why not?” The climate was set for change and it was happening. If the 70s lacked the polish of the 50s and the fervor of the 60s, they offered real opportunities as fields previously restricted opened up.

Sometimes people needed a little help, including artists and photographers. A lot of small organizations and co-operative ventures were born: the A.I.R. Gallery, Soho Photo Gallery, The Floating Foundation of Photography, and Professional Women Photographers. These efforts were grass roots because they had to be–there were very few established organizations where art photographers could exhibit, and for women artists and photographers to turn to. It was uncharted territory: a new frontier with a new, very creative type of pioneer.

Looking at these letters, many typed on a typewriter with a single courier font, you realize that information wasn’t an easy click away as it is today. The Internet was still the ARPANET, and these women had to buy and read photo publications, write letters, and mail them off. They had to want more for themselves–more options, opportunities and support. Joining a women’s photographic group was a huge step for them, but a logical one.

Throughout Women’s History Month, PWP is going to publish some of these letters and other documents from its archives. Though small in nature, they speak to larger truths. Isn’t that the history of women? Who through quiet strength and hidden lives have sustained others and made so much possible?

It’s good to remember that today’s opportunities were paid for by others’ struggles. It is good to honor those who came before, to understand the tenor of their time, and to remember that the work is not yet finished, that around the world many women still lack even the most basic freedom.

– Catherine Kirkpatrick, PWP Web Committee

30 By 30: Meryl Meisler / Via Wynroth

30 Women Photographers on the Women Photographers Who Inspired Them

A Blog Series in Honor of Women’s History Month, March 1 – 31

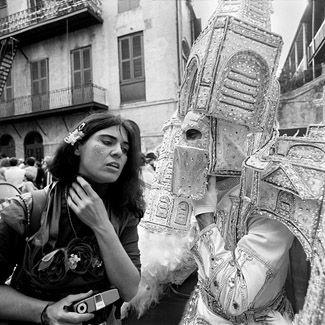

Meryl Meisler is a photographer and art teacher celebrated for her historic images of Bushwick, Brooklyn in the decades following the arson and looting of the 1977 NYC blackout. She has won fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts, Time Warner, Artists Space, CETA, the China Institute and the Japan Society. Her work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, the New Museum, the Dia Center NYC, MASS MoCA, and The Whitney.

Which woman photographer inspired you most?

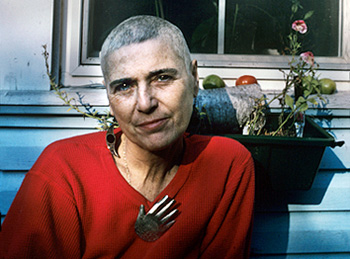

MM: Via Wynroth, the first Education Director of the International Center of Photography-through her life, profession, and our personal connection as friends.

How did you meet?

MM: In 1977 we were both houseguests of Michael P. Smith and decided to enjoy Mardi Gras together. I had a Norita Graflex 2 ¼, and Via had a plastic Diana camera with color film. We went behind the scenes to visit the Mardi Gras Indians, the floats, the Jazz club Tipitina, then went on a big crawfish-eating frenzy. We returned to New York separately, but didn’t go our separate ways. We’d become dear friends.

What did she teach you?

MM: Via used all kinds of media and cameras-the Diana, 35mm, and 4×5-like a poet. She also made beautiful collages in shadow boxes with lace, velvet, miniature dolls, contact-sized photographs, even a deep violet butterfly! Recovering from a bone marrow transplant, she managed to videotape herself.

She taught me the importance of laughter in art and life, that equipment is less important than vision, that photography is mysterious, and teaching profound. Also that passion and integrity are more important than ambition and breaks, that time and health are never a given.

How did she come to photography?

MM: Via was born in Paris on February 20, 1940 to Jolan Gluck, and Oskar Gluck, a renowned film producer forced from his native Austria by the Nazis. It has always been my suspicion that in order to survive, that she was sent to live with a family in Paris. If so, she was another type of Holocaust survivor, a hidden Jew. After WWII, she was reunited with her parents in New York.

Via studied photography at the Art Institute of Chicago with Barbara Crane, then moved to Ithaca, New York, married, and became a staff photographer for a local newspaper. Her photos of the student protests and Students for a Democratic Society were published in Life Magazine.

But her parents were close friends of the Capas, and when Cornell Capa was planning the International Center of Photography, he invited Via to start an education program. She was the daughter Cornell and Edie never had.

Working in the education department at ICP in the 70s, did she feel a need to help women photographers?

MM: Via was empowered to imagine and bring to reality a model, radical education program. At a time when photographic education was mainly geared for commercial purposes, she founded a program that emphasized vision and art. She sought out and hired the radical, the inventive, the legendary and lesser known, men and women alike. It was a time when the idea of hiring men and women on their own artistic and intellectual merit was far from the norm. It wasn’t an “old boys club€ at ICP with Via in charge. I don’t know that she felt a need to help women photographers in particular, but she hired a lot of women photographers.

Why do women photographers matter?

MM: Whoa!! Why do women matter? Why does photography matter? This would take a lifetime of study, a PhD, a truth serum, a novel and many made for TV movies, plus museum shows and investigative reporting. They just do.

Via eventually took leave from her full time position ICP and traveled to Mexico. She would return to New York to teach ICP’s Summersite Programs, and on one of those visits, learned she had breast cancer.

She stayed, and found new joy in a home upstate in Cornwall, one with a marvelous studio. Via had lots of plans in the works: a one-woman exhibit and a book about her beloved Yucatan, that has yet to be published.

Mrs. Glück survived the passing of her only child, carried the sorrow, and maintained the house and Via’s studio exactly as it had been. When Mrs. Glück passed away, a friend cleaning the Cornwall house found Via’s photographic work that was going to be thrown away. Via’s friend Patt Blue put a halt to that and flew in from Texas to rescue Via’s work. Patt beseeched Steve Rooney, the CFO of ICP, and the ICP collections department took Via’s negatives and archives. Patt worked night and day for weeks to organize, box and bring in Via’s life’s work to ICP.

I will never forget Via Wynroth. When my spouse Pattie and I adopted a beautiful poodle/bichon with wavy black hair we tried very hard to come up with a name. Then Via, with her beautiful black hair came to mind and we named her Via, in honor of Via Wynroth. I’m sure they would both enjoy each other’s company and be proud to share their name.

[This blog post on Via Wynroth is part of a series about contemporary women photographers taking inspiration from other women photographers. The posts are usually about how the "inspiring" photographer's work touched them and affected their own work. In most cases, this inspiration is "remote," from a great, but not personally known photographer to another photographer. But in the case of Via Wynroth, it was not a "remote" mentorship, but an actual friendship. Other people who knew Via have gently corrected the details of her life that were mentioned in Meryl's reflection of her, and we have tried to incorporate these. It is wonderful to know that people care about Via and remember her, and we give thanks to them. She truly was inspiring.]

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director

______________________________

30 By 30 blog series:

Intro: Dianora Niccolini / Women of Vision

Lauren Fleishman / Nan Goldin

Darleen Rubin / Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Dannielle Hayes / Diane Arbus

Meryl Meisler / Via Wynroth

Shana Schnur / Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Claudia Kunin / Imogen Cunningham

Gigi Stoll / Flo Fox

Robbie Kaye / Abi Hodes

Alice Sachs Zimet / Lisette Model

Juliana Sohn / Sally Mann

Susan May Tell / Lilo Raymond

Nora Kobrenik / Cindy Sherman

Caroline Coon / Ida Kar

Lisa Kahane / Jill Freedman

Karen Smul / Dorothea Lange

Claudia Sohrens / Martha Rosler

Laine Wyatt / Diane Arbus

Ruth Fremson / Strength From the Many

Greer Muldowney / Lee Miller

Rachel Barrett / Vera Lutter

Aline Smithson / Brigitte Lacombe

Ann George / Josephine Sacabo

Judi Bommarito / Mary Ellen Mark

Kay Kenny / Judy Dater

Editta Sherman / The Natural

Patt Blue / Ruth Orkin

Vicki Goldberg / Margaret Bourke-White

Beth Schiffer / Carrie Mae Weems

Anonymous / Her Mother

Sgt. Pepper Uncovered

This post was named to Photoshelter’s list of Best Blog Posts of 2011.

She’s always dressed like a babe: white trench coat with no sign of anything underneath, a clinging jumpsuit, a sparkly blouse that reveals far more than it covers. Then again, it was TV and ratings were involved.

When Angie Dickinson starred from 1974 to 1978 as Sgt. Leanne “Pepper” Anderson in NBC’s Police Woman, it was groundbreaking television. Those were the years women were pouring into the work force, and entering professions like law enforcement and photography that traditionally had been the provence of men.

But television always plays catch up to social trends, and glamorizes them with little regard for the truth. In the case of women entering the police, the reality was far tougher and more prosaic than TV land ever let on. Certainly their clothes, especially when going undercover, weren’t anything like Sgt. Pepper’s. But one photographer took a closer look at the real thing.

Jane Hoffer is one of those quiet PWP members who astounds you with her accomplishments. She has an MA and Ed.D from Columbia University’s Teachers College, and was working on her doctorate when she took an elective in photography that changed her life. While eventually she finished her dissertation (on the “Technical and Aesthetic Developments of the Photo-Essay”), she began taking photography courses at the New School, SVA and ICP, and in the mid 80′s went into the field full time.

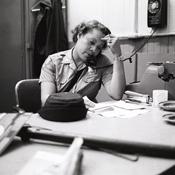

Hoffer has photographed Paul Newman, Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, and traveled with the Boys Choir of Harlem. While there’ve always been commercial projects to pay the rent, there’ve been others that were labors of love. “I used photography to put myself in places I couldn’t go without the camera,€ she says. And in the early 70′s she found herself riding with the police-an unlikely gig for a quiet artist who is also a practicing Buddhist.

Hoffer began the project in the 70′s when she belonged to a group called Women Photographers of New York (founded by PWP’s first president, Dianora Niccolini). Members would suggest topics for exploration and possible exhibition, and one topic was women at work. At the time, Hoffer was teaching photography at John Jay College of Criminal Justice where she knew a woman who was a Buddhist…who said she could contact a policewoman friend of hers who was also a Buddhist…who would be willing to let Hoffer ride with her and be photographed. Official permission was granted and the project got underway.

“In the early 1970′s police women were put on patrol. I was a young photographer and was fascinated by the emerging roles of women in police work,” Hoffer says. “I photographed them in their precinct houses, their patrol cars and at the firing range. I photographed officers, sergeants, auxiliaries, physical education instructors at the academy and emergency service women.€

While photography has traditionally been predominately male, there have always been great women photographers. Julia Margaret Cameron, Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White are a few who come to mind. But women in law enforcement had a tough time just getting in. While they’ve been a part of the NYPD since 1845, for many years they were limited to the role of “matron,€ with duties that included searching and guarding female prisoners, and working with youths. It wasn’t until 1973 that they were known as “Police Officers€ and were assigned to regular patrol duties due to the 1972 amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibited state and local agencies from gender-based job discrimination.

Even then, according to Kathy Burke, retired NYPD Detective 1st Grade and Past President of the International Association of Women Police, they were treated differently in large ways and small. For instance, while men had a 4 inch 6 shot revolver, women had a 3 inch 5 shot revolver. During target practice, each police officer had to get off 6 shots in a set period of time. Men could just fire their six shots, but women were forced to stop after 5 and reload, a somewhat tricky procedure, and still finish in the allotted time. The new women officers faced hostility from men in the department, and also from other women. Police wives protested when their husbands were paired with female officers. They feared amorous entanglements would ensue or that their husbands wouldn’t be as safe as they would be with a man. And women who had been part of the force in more traditional capacities resented the newcomers and the changing requirements of the job.

The job, says Detective Burke, is “filed with good times…filled with sad times. When the times are hard, they’re really really hard.€

In working on the project, Hoffer says she “learned a lot about myself and how I work with people. I eventually became an event photographer and it was probably these early years, working with women on the force, that helped me develop my “people skills.” I know when to charm and when to be invisible.€ She also brought her own peaceful karma to the project that began at the 13th Precinct on Manhattan’s East Side. Hoffer wanted to catch some action, but since police officers are not allowed to draw their weapons without justification, posing and set-ups were out of the question. So she went up to the 41 in the South Bronx (aka Fort Apache) on the night of a full moon…and nothing happened! That evening there were no incidents or events, just some very bored police officers who complained that Hoffer was a jinx.

But the danger is very real. While one of the women Hoffer photographed never drew her gun once in her entire career, Detective Burke was shot, and other women have died in the line of duty. The only thing that doesn’t quite live up to the dramatized versions is the outfit. But then it’s about much more than glamor. According to Hoffer, one of these early officers said “they faced more prejudice from fellow male officers than they did from men on the street. Because men on the street recognized and respected the uniform.€

I live near the Police Academy, and last week saw a female police cadet on the 23rd Street subway platform. Her face didn’t give out much and I thought about the isolation the earlier women officers suffered when they were 1% of the force. Then the cadet was joined by three other female cadets and a man who seemed to be an instructor at the Academy. They laughed and chatted. As people crowded onto the train, only one cadet managed to grab onto a pole. So the other cadets hung onto her and joked about bonding and being a family. They seemed comfortable with themselves and with each other.

Several times I thought about reaching out, asking them what it was like to be a female recruit in 2011. But every time I felt the urge to speak, I was reminded of the distance between us, between civilians and the police. The dark blue shirt and pants and jacket might not be as chic as Sgt. Anderson’s outfits, but it was The Uniform, and as such, commanded respect. No matter which sex was wearing it.

Police Commissioner Ray Kelly said that “the history of women in law enforcement dates back more than 100 years, but the most significant progress has been packed into the last few decades….Women are continuing to make history here, and have a powerful influence on the well-being of New Yorkers.€ The world moves forward, if slowly.

Jane Hoffer’s pictures will be on exhibit at the Police Museum in Lower Manhattan from February 8th through May 9th.

One of her prints, “An Officer at the Firing Range,” is in the PWP Archives.

- Catherine Kirkpatrick, Archives Director